The Teacher

Paris, 1979

It was obvious when she walked in the room that she was a force to be reckoned with. Standing at only 5’2” and in her late fifties, she marched to the chalkboard and wrote, Lorette Ankaoua. Turning toward us, she said “Welcome to the Alliance Française Paris. I will be your teacher for this three month study of the French language.”

A Canadian student leaned over to ask a classmate what Madame Ankaoua had said. In a stern voice, the professor responded. “No. This is a French class, and we will NOT be speaking English!” For three months, four hours a day, our professor worked hard to ensure that all 17 of us students could communicate with each other—Arabs with Jews, Peruvians with Germans. She seemed to have an incentive, a force beyond that of a normal instructor to guarantee that we could understand each other well.

It was 1979, a tumultuous time in Paris. As I explain in my upcoming book, Paris for Life, it was a year of riots, bombs, protests, and other forms of activism in the City of Light. But for Lorette Ankaoua, it was a time of relative peace. She didn’t talk much about her past, but did mention this—she and her husband came to France from Algeria. “As Jews, it was dangerous for us to live there. We came to France to be safe.”

By insisting that we speak only French, Madame was also forcing those of us from different nationalities and diverse points of view to work together. She taught at Alliance Française for over 20 years, retiring in 1983.

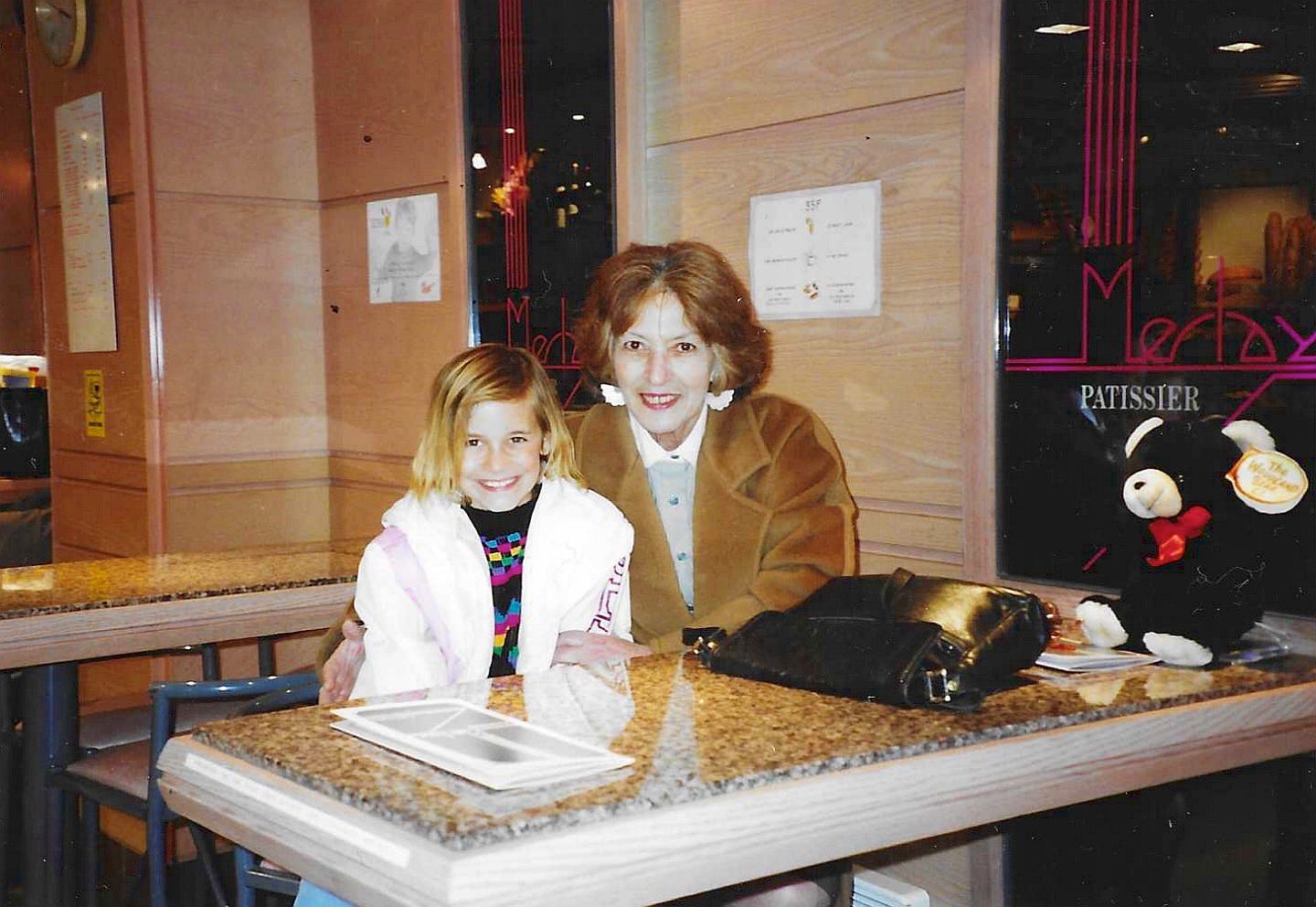

Over the years, my family and I visited her frequently at her Chatenay-Malabry apartment outside Paris. But forty years would pass before I learned her story from an oral interview she gave to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Born in Algeria in 1921, Lorette Ankaoua attended a boarding school and studied to be a teacher. At 19, she was told to leave because Jews were no longer allowed in the school. But she persevered, taking private lessons to pass the teaching exam.

In 1954, she survived a major earthquake and used a mattress to protect her children from the falling debris. Most of the housing in her Algerian village was destroyed. The same year, the Algerian war came to her town. Outside her window, members of the National Liberation Front were being executed, with one of her ex-students helping with the guillotine.

The Arabs she knew liked her, but there were many she didn’t know. Afraid to go to the casbah for fear of being recognized as a Jew, and afraid to shop at the European shops (many Europeans were being kidnapped), she had no way to purchase food. But she continued to teach. The young Arab children in her class smuggled bread to her in their dirty backpacks. It was all she had to eat.

In the early sixties, she escaped Algeria, joining her husband and children in Paris. Madame quickly found a job at the Alliance Française, the leading French language school for foreigners. I think of her often, and how she taught us to work together. I was thinking about her when the Jewish restaurant exploded moments after I walked past the front door in 1979, and when I read of the shootings in a Parisian Jewish grocery store in 2015, and each time there is another terrorist attack in Paris against any group who came looking for safety and peace.

Lorette Ankaoua’s lessons went far beyond teaching the French language. She taught us that by working together we could accomplish more than if we live in our own separate groups. And she taught me the importance of remaining positive, and to make a difference in the world regardless of what the world throws my way. And that is a lesson I will never forget.

For her story (in English) on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website, click here.

For her video (in French), click here.

This is a nice supplement to your book and gives insight to Madame Anakoua.

Wow! To find your article today was quite the blessing and miracle. Madame Ankaoua was my teacher in Paris in 1975-76. There are 4 of us who met in her class in ‘75 and we are gathering in Paris this fall to celebrate 50 years since we met in Paris. I did not know about her history. Is she still alive?

I am going to buy your book!